It took us to reach the fifth run of our one-month intensive course, with its fourth Public Defenses, 👉 to arrive at a point where some Final Works, presented by our most experienced students, were done at the level of real mini-research 👍—work that can already be seen as possible Research Topics for further studies 😃, possibly by a new generation 😁 of Nomad students and teachers. 😸

Among many presentations, we are highlighting two defenses in particular: those of Nikita Nikitin and Boris Babichev.

The work of Nikita Nikitin was devoted to Mass Protests in GEORGIA, analysed from the position of Protest Publics methodology, which was also developed previously in the course of Lilly O’Toole, devoted to Actor Publics and global protests, and from which Nikita likewise benefited.

To make a deeper study, Nikita introduced a Comparative aspect, choosing mass protests in neighbouring Turkey. This allowed him to highlight both similarities—both protests unfolded in an “unfree environment”—and differences, such as the much stronger 💪 organisational transformation of street action in Turkey into organised political opposition.

The reasons, deep roots, and consequences of these differences should, definitely, be explored further.

The Final Course work of Boris Babichev addressed, perhaps, the most challenging topic occupying social scientists and scholars of “State and Society,” or even the broader concept of CITIZENSHIP itself—directly connected to the centuries-long debate on CONSTITUTIONALISM.

Drawing on his own wonders 😉 through a consciously nomadic life, Boris asked ⁉️ how a thinking, professional, responsible human—who cares for others and wishes them well 🙏—might depend less on the greed and evil of political leaders in the countries where he happens to be born, live, and travel, especially when it is extraordinarily hard to change the entire “political environment” of a given territory in a given time.

This question connects to a search 🔎 for an identity 🆔 beyond a “country of one’s passport,” including a possible identity of “Global 🌍 Citizen,” where the balance of RIGHTS and Duties depends on how much each individual has contributed to the Global Community.

Needless to say, the topic is broad and challenging, but the consciousness of “global citizenship” is clearly rising 😉, and so is the demand for more research on it.

I am deeply proud 🦚 that both works were developed as the result of my “Harvard course” on Constitution and Citizenship, so we will definitely offer this course again next semester.

— Nina Belyaeva

Dean, Global Nomad University

Below you can find some detailed summary about mentioned defenses

___________________

Nikita Nikitin Defends Comparative Study on Freedom of Assembly in Georgia and Turkey

Why Georgia and Turkey?

Nikitin selected Georgia and Turkey because both countries hold regular elections yet face accusations of democratic backsliding. Georgia’s opposition recently shifted toward parliamentary boycotts and street rallies, while Turkish opposition parties continue to contest elections even after years of repression. Comparing these paths, he argued, helps activists and policymakers think more strategically about when to work inside formal institutions and when to apply outside pressure.

Evidence at a Glance

- Turkey (2013-2025)

- ≈ 8 500 injuries and 6 000 detentions linked to protest events

- 1 700+ NGOs closed by emergency decrees after 2016

- Freedom House score: 33 / 100 (Not Free)

- Georgia (same period)

- ≈ 300 injuries and 650 detentions

- No mass NGO closures to date, but proposed “foreign agents” legislation signals rising pressure

- Freedom House score: 58 / 100 (Partly Free)

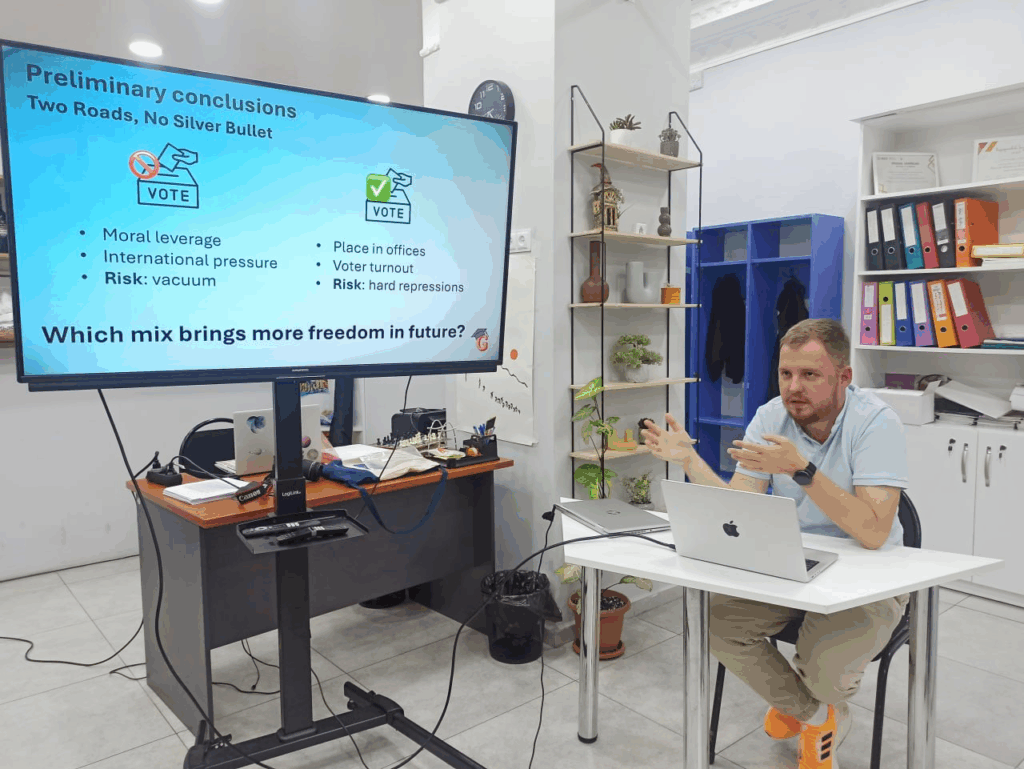

Nikitin combined these figures with qualitative analysis of landmark demonstrations—Gezi Park (2013), Georgia’s “Gavrilov Night” (2019), the March 2023 protests in Tbilisi, and Turkey’s 2025 rallies after Istanbul’s mayor was jailed. He concluded that mass protest can still influence policy in partially free systems (Georgia), whereas in more repressive settings (Turkey) electoral participation remains a crucial—if risky—lever for change.

Key Takeaways

- Boycott vs. Engagement – Georgia’s boycott strategy draws strong international sympathy but leaves parliament uncontested; Turkey’s engagement keeps an opposition voice yet exposes leaders to arrest.

- Numbers Matter – Tracking injuries, detentions, and NGO closures clarifies how quickly civic space can shrink.

- No Single Formula – Successful movements often combine protest visibility with strategic use of institutional openings.

The defense ended with a forward-looking question: “Which mix of tactics will open more civic space by 2028?” Judging by the animated Q&A that followed, the audience left with plenty to think about.

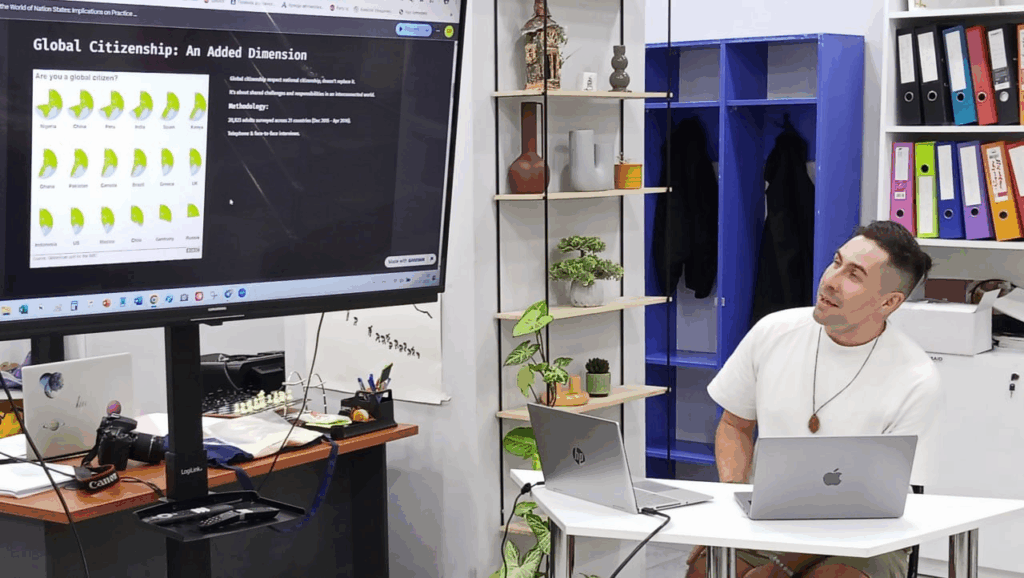

Boris Babichev on “Global Citizenship in the World of Nation-States”

What was asked

Boris started with a simple, unsettling question: “What can an ordinary person do when the nation-state that grants their rights is the same state that abuses them?” National citizenship gives us passports and laws, yet it also ties us to mistakes and injustice we did not choose.

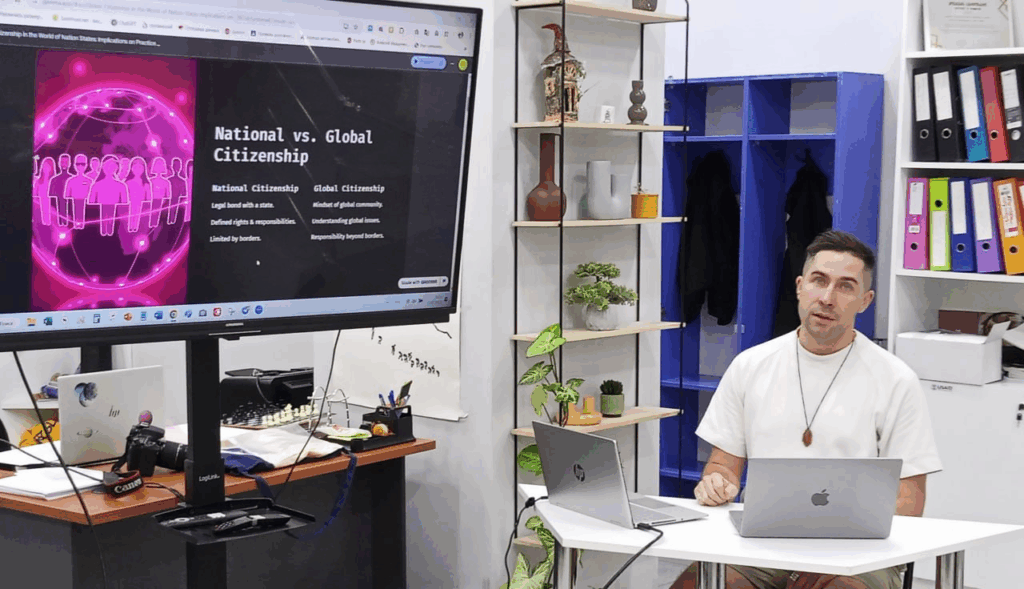

What was approached

- Conceptual frame: Boris contrasts national and global citizenship. National status is a legal bond, fixed by borders; global citizenship is a mindset—knowing the planet’s problems and feeling responsible beyond borders.

- Method: He mixes classic authors (Nussbaum, Habermas) with a 21-country survey of 20 823 adults that maps how people already see themselves as “world citizens”.

- Problem cases:

- When states mismanage economies—Russia’s 2024 ruble crash that cut real incomes by 20-25 % in one night.

- When states strip documentation—Belarus’s 2023 decree forcing citizens abroad to fly home for a passport, risking statelessness.

- Practical tests: He shows how some solutions emerge outside governments—Lithuania and Poland issuing travel papers to Belarusians, or crypto projects promising self-sovereign ID (with a warning tale: the failed Decenturion “blockchain state” scam).

What he found

- Layered identity beats single passport. People can be national citizens and members of trans-national networks, choosing tax regimes, human-rights venues, or climate projects that match their ethics.

- Global citizenship is voluntary and moral. It’s built not on duties imposed by law but on contributions driven by empathy and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

- Decentralised movements matter. Boris argues that a holacratic, 100 % decentralised web of activists can offer “a non-violent alternative to dictatorship,” because power is spread, not hoarded.

Why it matters

For scholars: The paper reframes citizenship studies around resilience: how individuals keep agency when state systems fail.

For practitioners: It points to concrete work—issuing alternative travel documents, using crypto for censorship-proof savings, or aligning companies with planet-wide goals.

For GNU: The project grows directly out of Nina Belyaeva’s “Constitution and Citizenship” course, showing how one-month learning sprints can spark research worth scaling up next term.

Babichev’s closing line sums up his thesis: “Global citizenship is not where you belong, but what you stand for and contribute.” The audience left weighing whether that mindset can indeed shield people from the next economic shock or passport crisis.